Professor Godfrey Chan of the Department of Paediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, Li Ka Shing Faculty of Medicine, The University of Hong Kong, has been passionate about medical science since a young age. Spending a decade to realize his dream in becoming a paediatrician, his journey was by no means easy. Accompanying paediatric patients and families in the fight of severe conditions and walking side by side in the exploration of life with his own autistic son, Professor Chan is ready to share his insights on living in the moment as the true meaning of life, “Every cloud has a silver lining.”

The diligent pursuit of his dream of becoming a doctor

Professor Chan’s passion for biology and his life goal of becoming a doctor stemmed from a young age. A classmate of his once wrote in the classbook, stating that he would study anything related to medicine, be it dentistry, Western medicine, Chinese medicine or veterinary medicine. As he had taken his secondary education in a six-year CMI secondary school, he was not qualified to enter the local medical school upon graduation. While affluent students chose to study medicine in Europe and America, he opted for dentistry in the Philippines, where his passion, hard work and talent garnered him good grades. He then stumbled upon hospital dentistry which sparked his dream of working at a hospital one day. “I need to be mentally challenged as repetitive tasks are, for me, tedious and restrictive. I also had teachers questioning why I chose dentistry instead of medicine with my good grades.” Thanks to his teachers’ undue encouragement, Professor Chan finally pursued medicine after graduating from dentistry. Despite relatives’ challenging comments on the unthriftiness of investing even more money on furthering his studies, his father stood by him as he continued to pursue his dream.

Failure is the greatest teacher

Professor Chan returned to Hong Kong to complete his dental licensing exam while furthering his studies in medicine. It was a huge burden for literally anyone, yet the difficulties he encountered prompted him to hone himself. “I received the honour of ‘Outstanding Dental Student of the Year’ when I graduated, but I failed my licensing exam twice in Hong Kong. I learnt from the experience and was able to pass every medical and specialist exam on the first attempt thereafter. The meaning of failures is defined by the way you take them.” Understanding that every journey is dotted with obstacles, Professor Chan has long grasped that he must acknowledge, accept and stay true to who he is before he could truly realize his potential and reach his goals. “I spent 10 years studying dentistry and Western medicine. When my peers had entered the workforce after four years of university, I was still in school. Studying medicine is no easy feat. It takes a lot of perseverance to follow through.”

Follow your heart

After graduating with a degree in medicine, Professor Chan was assigned to an internship in the orthopaedics department at a local hospital. Repetitive daily tasks made him question his dream of becoming a doctor. He was particularly doubtful about his career path when he was assigned to the same hospital three times in a row. He decided to make a change and took the initiative to apply for an internship at a different hospital. As a result, he was assigned to Queen Mary Hospital where he met his first mentor, Professor Yeung Chap Yung, who persuaded him to become a paediatrician instead of a surgeon. Professor Chan is grateful for the decision he made, “I was also interested in paediatrics and had the chance to come across a lot of rare diseases and learn from excellent doctors during my internship at Queen Mary Hospital. No matter how challenging work may seem, I always feel happy and satisfied at the end of the day, which is the perfect indicator on whether I have made the right choice for myself. Follow your heart – it is that simple.”

for yourself.”

The ups and downs as a paediatrician

All careers alike, behind the glory of a doctor are countless bittersweet experiences. “While I have delightful moments such as curing serious conditions and enjoying the surprise birthday party organized by my patients with thalassemia, whom I have known since they were born, there are also regretful points in my career that I have to live with. For instance, there was a case that our team advised against parents’ decision to treat their child in the US. When the patient relapsed, one of the parents threw a can of soda at me and furiously told me to go back treating rats in the lab. When a mistake is made, we must address and admit. On the other hand, if anyone claims that no mistake has ever happened in his/her entire life, it will only make me wonder how little he/she must have done – that would be, way far from enough.”

Paediatricians meet children with different backgrounds and personalities on a daily basis. Acute observation and endless patience are keys to a good diagnosis. “Since children encounter different developmental milestones at different ages, the biggest challenge about being a paediatrician is that we must determine their progress based on experience. Children begin to develop stranger anxiety from seven to nine months old – how can we keep them relaxed during consultation? A five-year-old child tends to ignore you when you ask them to breathe in and out. We must consider their behaviours and reactions and cope with them accordingly.”

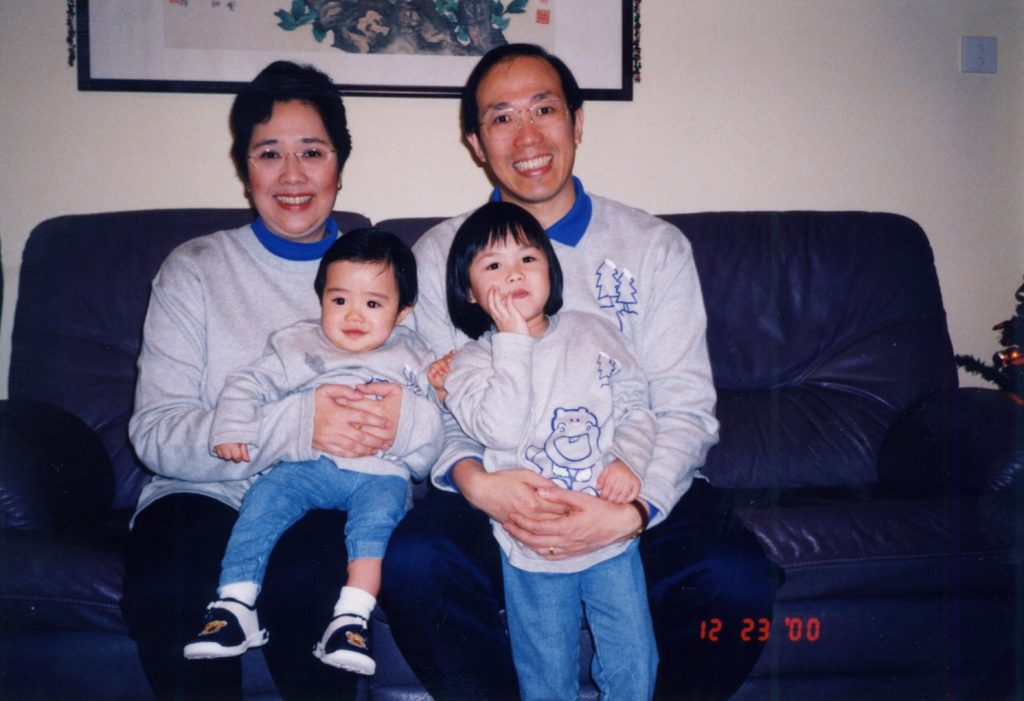

Empower parents with his own experience

Professor Chan is known for his heartfelt empathy for parents and caregivers of sick children. He is able to treat his patients’ family with cordiality and compassionate demeanor not only because he is an outstanding doctor but also a caring father. With a child that requires special care at home, Professor Chan shares the worries of most parents of sick children. “Like most parents, I often worried about the sickness and future of my autistic son, until I came across a paragraph in a book: ’If the mountain will not move, build a road around it. If the road will not turn, change your path. If you are unable to do so, just adjust your mindset.’ Indeed, we cannot move mountains nor avoid the obstacles and difficulties that come our way, but we can accept our children’s congenital disorder as an imperfection and seek treatment; if there is still nothing to be done after that, we can simply adjust our mindset.”

Professor Chan candidly revealed that he and his wife once had high expectations on their children and it had taken some time for them to accept their son’s condition. Since then, they have enjoyed countless precious, wonderful moments their son has brought them. “Our son has brought us immense joy albeit his condition. Instead of dwelling on negative thoughts, we decided to live in the moment, cherish our children and live our lives to the fullest. No one can be sure about what the future will bring. All we can do is to try our best to plan and be optimistic. I have met young patients suffering from much more serious conditions but it does not stop them from being blessed with a happy family. Every cloud has a silver lining: it is all about your perspective.”

Words for parents and teenagers under the pandemic

Professor Chan reminds parents to pay attention to their children’s health besides fighting the challenges at work and being cautious with shielding the family from the pandemic. “Many patients have delayed their treatment during the COVID-19 outbreak. For instance, children with osteosarcoma may fail to recognize their symptoms in time due to their sedentary lifestyle at home. Parents must pay attention to any abnormal behaviour or symptoms in their children to ensure timely diagnosis.”

With regard to information overload that came with the pandemic, Professor Chan emphasizes the importance of critical thinking and good analytical skills. “Young people should not be hesitant to ask questions, think, analyze and dig deep for answers. Critical thinking is essential, especially in this era of overwhelming information. It has become a common practice for people to seek answers online, but how can we be sure that the information is correct and does not come with bias propagation? We must learn to distinguish truth and falsehood.”

Professor Godfrey Chan made the following remark when he attended the launch ceremony of the “We Care · Fight Haemophilia” campaign as an officiating guest, “Lacking the clotting factor in their blood, haemophiliacs’ body would not be able to stop bleeding if hurt, which would in turn cause haemorrhage or large bruises. The symptoms are rarely identified until toddler age, when they are prone to falling and forming bruises. Parents should immediately consult a doctor if they detect abnormal bleeding in their children, be it in the muscles or in the joints. Doctors will prescribe

medications with coagulation factors to keep the conditions under control.” While parents of haemophiliacs may ban their children from participating in PE lessons out of fear of injuries, Professor Chan does not consider it necessary, “As preventive treatments – such as the new long-acting coagulation factors – are available nowadays, I would encourage patients suffering from haemophilia to take part in PE lessons and live a normal life.”